This year’s Mooncake Festival was celebrated on 21 September, or the 15th day of the 8th month of the Chinese lunar calendar. It is also known as the Mid-Autumn Festival although it is definitely Spring here in Australia. Celebrated by most Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese communities world-wide, I was surprised to receive a tin of mooncakes this year from my bank manager. He did not understand the story behind mooncakes, so he asked me. Luckily, I had Googled the night before our meeting and impressed him with my knowledge. There is the legend about beautiful Chang’e flying to the moon after stealing the elixir of immortality from her husband, the archer Hou Yi. He was the hero who saved the world from global warming by shooting down nine suns. The other legend about mooncakes originated during the end of the Yuan Dynasty when Ming guerrillas communicated with one another through hidden messages in their mooncakes. The messages would then be eaten with the mooncakes to destroy any incriminating evidence. I was hoping to link this custom to the Water Margin, but unfortunately the Ming uprising occurred a hundred years after the civil wars of the Water Margin.

It was Wu Yong’s wife who first told him the story about Wu Gang, on account they both share the same name. “Why are you so “bo uak tang?” (not lively in Hokkien) she asked Wu Yong many years ago. “Why aren’t you like Wu Gang?” she added, unaware he was seething silently. Wu Yong’s other name is Wu Gang, it is common for a Chinese to have two names and a surname. The Wu Gang who lives on the moon is famous for his tireless attempts to chop down an osmanthus tree. We know that if such a tree can exist in nature, it won’t be just a single tree. It would be a park full of trees that produce white and orange blooms with the alluring scent of ripe peaches. Little did Wu Gang know that the osmanthus tree he is tasked with cutting down is a self-healing tree. Wu Gang was sent to the moon during the Tang Dynasty in the 7th century – apparently to achieve immortality. It is somewhat annoying to learn that the story about Wu Gang isn’t real. For that, we ought to blame Neil Armstrong and his Apollo 11 crew. That’s one small step for man, one giant blow to Wu Gang. A futile toil in a park on the moon. That was how I thought of Park Moon, the next hero in my Urghhling Marsh brotherhood.

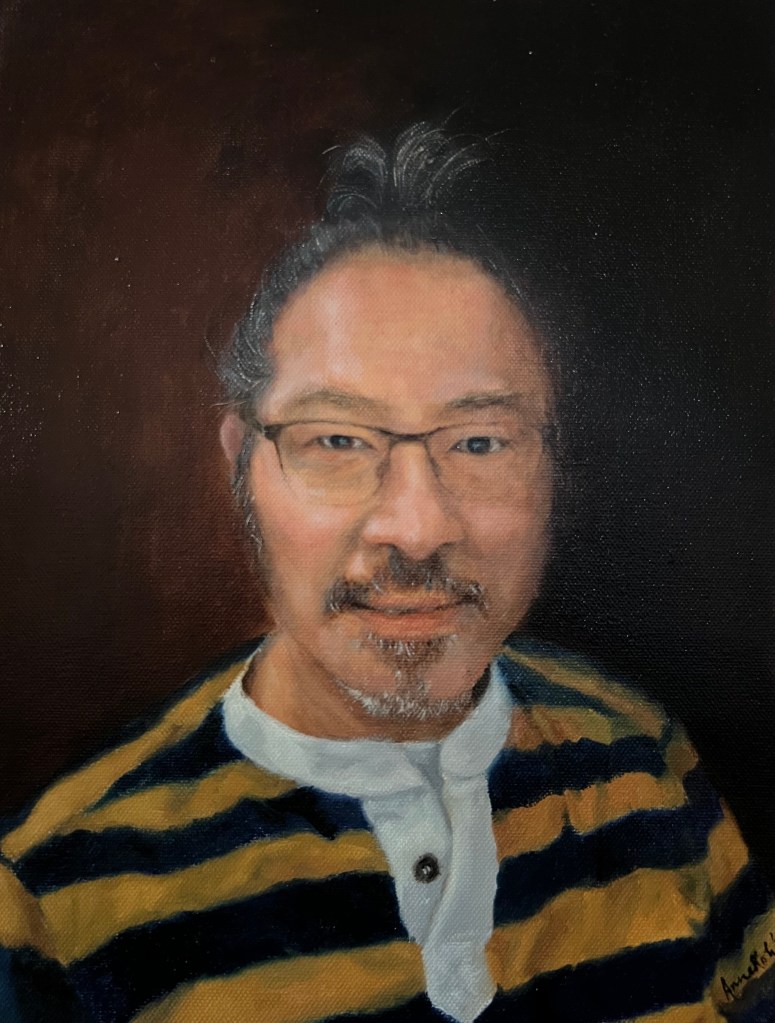

Park Moon is fairly tall with a somewhat fair complexion. A handsome man with meticulously groomed hair, his face is broad but it is not a moon face. It isn’t round and it isn’t pock-marked with crater-like depressions like those on the moon. For a top-tier executive who had served his employer globally for over three decades, he does not have the coldness of a bank manager or the sneering scowl of an art critic. He is a kind man who cherishes his parents’ love and upbringing and acknowledges the big part his teachers helped shape his destiny. A loyal friend, he remains true to his schoolmates and work colleagues, some of whom he continues to mentor. Park Moon’s surname is Moey. On one of his business class trips to Europe, the air stewardess referred to him as Mr. Money. Park Moon placed his forefinger to his thin lips and told her the “n” is missing in his surname which was why he had to go earn some money. It was this quest to pursue his lofty ambitions to be a successful man with loads of money that reminded me of the futility of Wu Gang’s mission on the moon. All the money in the world may get us all the consumer goods we want but as John Lennon said, all we need is love. Park Moon paid a big price for pursuing his dreams. His marriage to a Singaporean lady ended in divorce and he lost touch with their son, a smart young man who graduated from NUS as a Chemical Engineer.

Today, Park Moon has mellowed and is more content with life. Happily remarried to a Convent Datuk Keramat girl who was once his ex-neighbour, he has two lovely daughters with her – one is a doctor and the other is in the biotech field. “I am exchanging money and perks for happiness as well as to prolong my life with less stressful work. Stepping down from a high position to a lower post can be painful and discomforting initially, especially in terms of pride,” he said. He is right. No good being Wu Gang for the osmanthus tree cannot be chopped down; all the rewards and status cannot buy us happiness and health. “This is one of the best decisions that I have made in my life,” he said, in a serious voice.

Happiness is my new rich, inner peace my new success. Health is my new wealth and kindness is my new cool.

Moey Park Moon

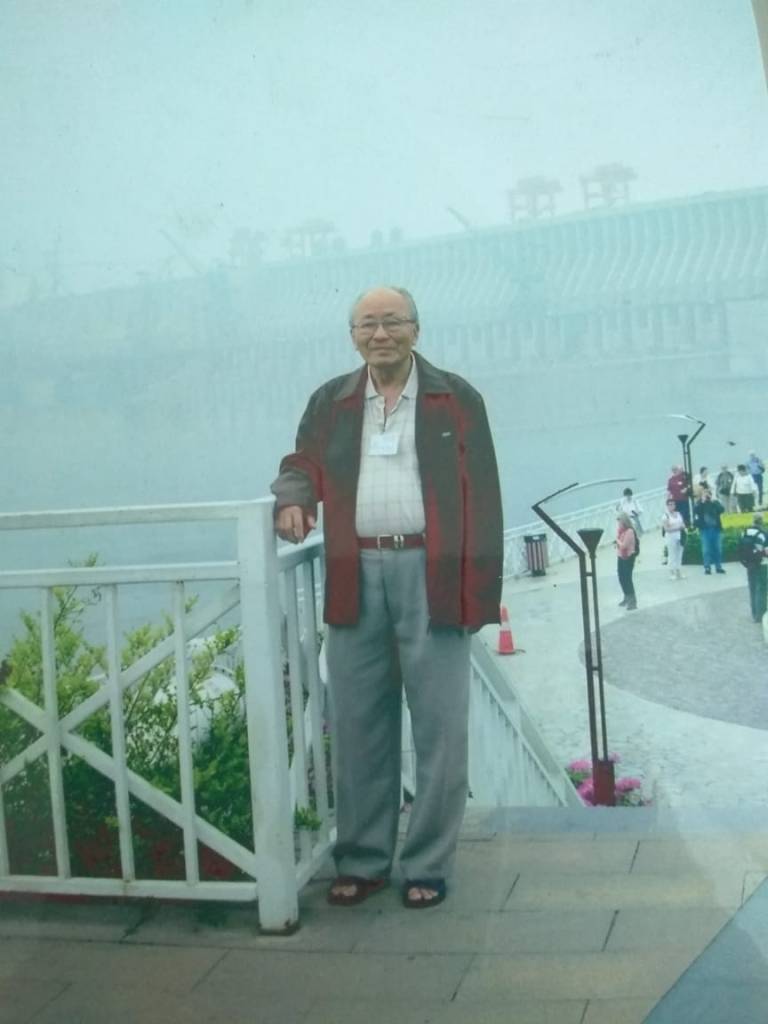

Park Moon’s grandfather spent a year or two in the US working on the railroad. He was smuggled into the country as the Chinese Exclusion Act was enforced in 1882. To avoid detection and capture, he had to wear socks only, to keep the noise level down. Movements and hikes were done strictly in the dark. With the money saved, he went back to China and built his house. His second attempt to re-enter the US a few years later was foiled and he was forced to return to China. That was when he and his four older brothers had their sights on Malaya. They arrived in Malaya in the early 1900s, and settled in the Kulim-Machang Bubok-Bukit Mertajam area. They were from Toishan, a county in the Pearl Delta area of Guangdong. Park Moon’s grandpa was in the woodworking / carpentry trade.

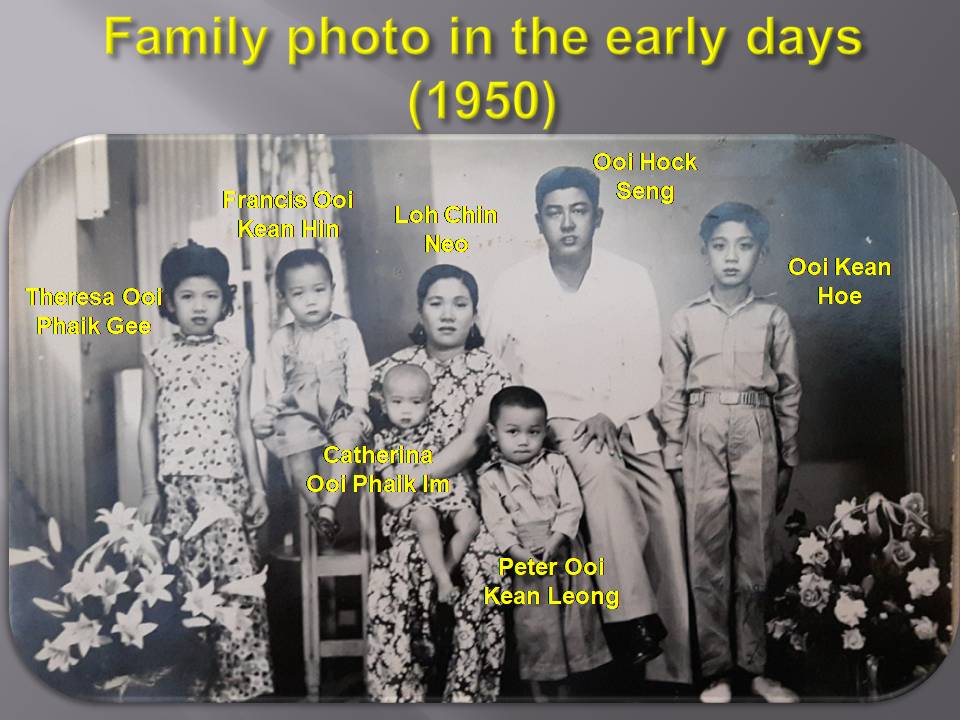

Park Moon’s father, Moey Hua Cheng, was born in 1921 in Kulim, Kedah. He was the second son, but from the father’s second wife. “One of my sisters told me that after he had passed away,” Park Moon said, divulging a once tightly-held family secret. His father’s mother was chased out of the house by the matriarch, the first wife. Hua Cheng was brought up by his stepmother. He studied till Standard 3, which was a big deal in those days in Malaya. When he was in his late teens, he was employed to work in a goldsmith and pawn shop, then partly owned by a distant cousin. “He married mum in 1940,” Park Moon continued. They moved to Penang after the war where he worked as a shop assistant for Cheong San Goldsmith at 43 Campbell Street. “Dad worked there till he retired at 72,” Park Moon said, an acknowledgment that it was the norm in those days for a person to work only for one boss in a lifetime. Despite his short time in school, he could speak, read and write Mandarin very well. He was talented at Chinese calligraphy and was the go-to person if anyone required proper Chinese writing for a big occasion. He was also fluent in Malay and could write Jawi well, and as he was also trustworthy, he helped retain a sizeable repeat business from the Malay community. They were mostly farmers who happily spent all their earnings after their harvest, and then a few months later would return to the shop to pawn their jewellery for needed cash; a cycle they repeated every year.

Park Moon’s mother, Kong Kui Yon was a foster child raised by a Hakka family. A year younger than her husband, her marriage to him was match made. She was eighteen, of child-bearing age and therefore much sought-after. By the time she was forty in 1962, she had borne eight children. She used to talk about her real mum but never mentioned her father and her other real siblings. In those days, they treated birth parents and siblings as real, adopted ones weren’t. Probably she never knew them. She was brought up in the Kulim-Lunas-Machang Bubok area but didn’t attend school. Her role then was to do the housework and tap rubber for the foster family. Despite her illiteracy, she learned to read some Mandarin. She was a mentally strong and capable woman, pulling the family together through her skills as a fantastic homemaker -juggling the meagre budget and making sure that there was always food on the dining table and clothes for her children to wear. “The clothes were hand-me-downs from good neighbours and friends that mum somehow was able to alter and make good again,” Park Moon said. Besides helping her husband make gold bracelets till late at night, she also supplemented the family income by washing clothes for others. Once or twice a week, she would join a group of women in washing the Penang ferries as well as cutting or removing the overhang threads from jeans produced by a knitwear factory near their neighbourhood. Park Moon fondly remembers his mother’s excellent yong tau foo (Hakka stuffed tofu) and other Hakka delicacies as well as fantastic Cantonese dishes and soups.

It is fine to wear old clothes that need mending. The important thing is that we did not steal them.

Kong Kui Yon

As a shop assistant, Hua Cheng earned about $150 per month. This was never enough to feed his family of eight children. The eldest is a boy, born in 1941, followed by four girls and then three boys. Park Moon is the sixth in the family. Before 1964, they all lived in a rented room in a house occupied by three other families who were also tenants at Lorong Susu (off Macalister Road). The room was so small the older kids had to sleep in the common corridor, which still left many young ones sharing the bed with their parents. How Hua Cheng and Kui Yon continued to satisfy their sexual needs without waking up the children deserved annual accolades. In 1964, Hua Cheng and his younger brother managed to pay a deposit for the purchase of a single-storey terrace house in Green Lane area, with the $2000-$3000 given to them by their stepmother as “a token of goodwill” upon her death.

Education is the only way out of poverty. Have a good life, be respectful and kind.

Moey Hua Cheng

Hua Cheng drummed into his children that education was the only way out of poverty for poor families like them. Unfortunately, to his big disappointment, the four eldest children were not so good in their studies. They attended Chinese-medium schools due to his patriotism for his father’s motherland. Mao Zedong could do no wrong in his eyes and he did not want his children to lose sight of their culture. But, being from the Chinese stream, they ended up working in local companies run by Chinese families and were therefore lowly paid. Hua Cheng began to believe that children in English-medium schools had better career opportunities, thus sending his next four children to be taught in English. He was very strict with them. Getting 80 marks in weekly tests was never good enough. A score of 90 would only earn the question “why not higher?” Like many kids in those days, Park Moon did not attend kindy and therefore could not read or write at all when he began his school life. Despite the poor start, he came ninth in class overall and that secured him in the top class from Standard 2 to Form 3. Throughout school he was an average student except he got a duck in his Form 1 English test. A student’s mark would begin at 40 out of 100, for one mistake. A second grammatical or spelling mistake earned a 20 point deduction. Park Moon’s command of the English language improved in leaps and bounds after that trauma. He did not tell me but I suspect his dad caned him. The good thing about being an average guy was that he could get along with both the more academically inclined classmates as well as the mischievous and street-wise types who were known as the “kwai lan kia”. Park Moon’s class nickname was “panjang” (long in Malay) because his scrawniness made him seem taller than most even though he was not the tallest.

Park Moon was a reasonably well-behaved boy who kept a low profile, yet he was caned three times by the headmaster, Brother John. One of the canings was rather frivolous – he was called out for walking on the grass even though there was no “Do not walk on grass” sign. The other two occasions were for being at the wrong place at the wrong time. Things got a bit rough among the boys playing marbles during recess and he was punished for their transgressions. But the one incident that Park Moon will never forget was his detention by his Standard 2 Form teacher for not understanding her instructions to complete a workbook exercise despite her numerous explanations. So she lost it, grabbed his hair and banged his head hard against the desk. The poor boy was too shocked to cry and too afraid to tell his father whose unshakeable belief was “Teachers are always right”. In school, Park Moon was known as the History King, being the top student in the subject. He got into SXI’s Form 4 Science 1 after better than expected results in the LCE. Science 1 boys were daunting to mix with. He perceived them to be smarter. He did not require his sense of inferiority to be the excuse to leave SXI for the Technical Institute (TI). His father saw technical education as his path to a better future. So, he pleased his father and enrolled in TI instead. Like most of his friends, he failed Bahasa Malaysia in the MCE and had to repeat it. Upper 5 was his St. Paul’s moment. He started attending church and eventually became a Christian. He passed his MCE this time with flying colours. After a year in Lower 6 Form, he arrived in Sydney, Australia with $3,000 in his pocket. It was all the money his father had. “So, make it last till you find a vacation job,” Hua Cheng said to his son. But to young Park Moon, it sounded like “swim or drown”.

Park Moon appreciated the gravity of his situation and was very careful with his finances during his matriculation and first year in Uni. For lunch, he survived on a 250ml carton of milk and a meat pie. Every day. I did not tell him but Wu Yong, another brother of the Urghhling Marsh lived on a 250ml carton of milk and a strawberry jam sandwich. Every day. Park Moon’s room was spartan. Book shelves, a study chair and a single bed with faulty springs were bought from The Smith Family which sold donated or used goods to raise money for children’s charity. During a hot and dry summer in his matriculation year, he had a difficult four weeks – knocking on factory doors from Rosebery to Parramatta looking for a job, feeling more and more desperate by the day. Then out of the blue, an Indonesian senior whom he barely knew introduced him to Fritzel & Schnitzel, a restaurant in Hunter Street for a kitchen hand job. The restaurant had just been taken over by a Lebanese family who fled the civil war. Within two weeks, he became the second chef because the owner and his Lebanese chef got into a very serious argument and the chef stormed out in a huff. In his second summer, he got a job in Rosebery – assembling one-armed bandits. The factory workers were migrants and refugees (Vietnamese, Chileans, Croatians, Serbs, Greeks, Italians, Turks, etc). The Croats didn’t like the Serbs, the Greeks hated the Turks and everyone called the Italians wogs. Working in hot and crammed conditions with them was torture. They were mostly bigger, taller and smellier than Park Moon, whose nostrils were just at the right armpit height of his garlic-loving colleagues who seemed to skip their daily baths. A Vietnamese shared his horrifying experience fleeing the country by boats deemed unseaworthy and the many obstacles and traumatic experiences exacted by pirates before they were able to reach Australia.

In his third summer, he got a job at an ice factory at the Pyrmont fish market. It was a one-man show, but would have been a physically demanding job even for two. In the morning, he had to make three to four runs per hour to the fish auction market, delivering five pallet loads of ice each time, using a manual lifter. The pallets loaded with ice were stacked up to his chin level. When the auction hours were over, typically by 12 noon, he then had to bag party ice and store them in the freezers, and when they were full, he stored them in a 40-ft container parked outside the factory. A typical day started at six in the morning – catch the no. 273 bus from Randwick to Pitt Street, then a ten-minute brisk walk to Pyrmont. His day finished at 10 at night. Sunday was the only rest day. He got paid well, for a uni student, but he also got stomach ulcers for missing his meals. It did not make sense why the boss would employ a weak-looking Asian boy for such a physical job. “Why me and not one of the stronger white guys who were in the queue?” he asked his boss. “Because you were the hungriest,” he said simply. In his fourth summer, he was required to do his industrial training at one of the shires in NSW which was quite close to the Queensland border. It was a good experience staying with an Aussie family. The family would drive him to ‘nearby’ Inverell on Saturday which was a good two hours drive away, and in return, Park Moon would cook a Chinese lunch for them the next day. He also tutored the family’s daughter who was in Year 6 or 7. The father would reciprocate and teach him golf and lawn bowling while the son, who was about seventeen years old, taught him archery.

In December 1983, Park Moon completed his double-degree course in Science and Engineering at the University of Sydney. He was promptly recruited by Singapore’s Mass Rapid Transit Corporation to work on their new MRT system. After six years there, he felt he had learned enough field work in civil and tunnel construction stuff and electrification works. He then moved on to the insurance industry, and was trained as a Risk Engineer with FM Global. He loved the opportunities to travel worldwide. “With full perks, executive suites in 5 or 6-star hotels and always Business Class!” he said candidly. One day, he could be at a Newmont mining site in remote Indonesia and the next day, in a super dust-free room like in a TSMC semiconductor wafer fab in Taiwan. Essentially the job exposed him to all kinds of industries – power plants, semicon fabs, pulp and paper mills, etc. More importantly through all this, he got a global network of friends. As his father used to say, “Why make enemies when you can make friends?” His first trip to China was in the winter of 1991. The feeling was unreal the moment the plane touched down in Beijing – somehow it felt like a home-coming for him even though that was the first time he stepped on the land where his grandfather was born. “I was joyous, I could feel the tears in my heart,” he said. There were no streetlights in Beijing- only the light bulbs in the shops gave some dim light. The main shopping area was however full of people. The drive from Beijing to Tianjin was uneventful. The roads were very wide, but empty of cars.

Instead, there were miles and miles of people in drab grey clothes on their bicycles being passed by a few tractor driven carts. The country was poor, the countryside dismal. Beggars trudged the streets pitifully, those without limbs sat on the roadsides, busily swatting at flies. He could see people carving blocks of ice from the frozen rivers and ponds. When he arrived at Tangshan which was hit by a huge earthquake in 1976 with the highest number of casualties on record, the factory had put up banners at the main gate to welcome him. Once the main gate was opened, as if prompted by a conductor, the factory employees started clapping and singing “Huan ying, huan ying” like a 1000-strong choir of sixteen voices. Park Moon found out later that the plant was hardly producing anything.

On his second trip to China, Park Moon got into trouble with the local authorities. It was in January 1993, during one of the harshest winters there. He was smuggled up the train from Changchun to Harbin without a train ticket. The plant manager had either forgotten or could not buy the ticket. Having boarded the train at the depot one stop from the train station, Park Moon thought he was provided with a spacious First Class cabin. But, when the train stopped at the train station, he soon realised he was in a six-person cabin and he was the seventh without a ticket. The temperature outside was minus 20 degree Celsius. The icy cold conditions motivated Park Moon to rustily argue in poor Mandarin with the train conductor whose strong Manchurian accent provided his errant passenger with a good excuse to plead ignorance and feign being insulted. The other six passengers relented after a rowdy few minutes and made room for the non-paying guest. The compromise was good enough for the conductor to extricate himself from the cabin without injuring anyone’s pride. With a little whimper, Park Moon bowed respectfully and said “Xie, xie, thank you.”

Park Moon is one of the nicest guys I know from my school. In 1996, as he was waiting for a table at the Red Lobsters Restaurant in Toronto, an elderly man came up to him and asked if he could share his table. Park Moon turned around and saw a man with a noble face and a bad posture. He looked decent enough and smelt clean, although his jacket looked slightly threadbare and his pants were clearly in need of a hot iron. “Sure, fine,” Park Moon replied and signalled to the waitress to set the table for two instead. When asked for his order after being given enough time with the glossy menu, the old man told the waitress he was with Park Moon, and to let Park Moon order for him. A free rider! Park Moon thought to himself.

“Would you like a glass of red wine?” he asked his uninvited guest. “I’m ordering a T-bone steak for you,” he said in a soft warm voice.

“I will have a lobster,” Park Moon said to the waitress and smiled sweetly as he closed the menu.

When their meals arrived, the elderly man did not hesitate to pounce on his steak. He ate the medium-rare meat like a man who had just disavowed his vegetarianism. Meat, glorious meat,” he seemed to be humming to himself as he emptied his plate in a blink of an eye. He placed his steak knife and fork side by side at the 4 o’clock position, signifying he had finished his meal. But, Park Moon had barely started pulling at his succulent eight hundred gram Maine lobster. Suddenly, the elderly man leaned forwards and yanked a claw from the lobster with his deformed fingers that were riddled with arthritis. The meaty claw flew off the table to Park Moon’s dismay and utter shock. Park Moon stepped off his side of the table to pick up the claw. As he bent down, he noticed the restaurant’s carpet, once freshly laid and springy to the feet, were discoloured and heavily-trodden with many small but visible bare patches. Park Moon returned to his seat with the claw pincered by his right thumb and forefinger. The elderly man asked if he could still have the claw. He broke into a radiant smile when his host offered him the whole lobster instead. Park Moon had lost his appetite.

He left his position as Engineering Manager after ten years with the company when Marsh (a major global insurance broker listed in NYSE) came calling. Park Moon became the Managing Director of the risk consulting business unit covering Asia. The company was flying high, so to speak, and he was doing exceptionally well personally, until Spitzer (a US attorney in NY) came along and started to haul-up brokers for non-compliance on financial and accounting misdeeds. As they say, all good things must come to an end and the company came under a lot of pressure from shareholders and market analysts. He called it quits after ten years with Marsh and joined their competitor, AON, also as the Managing Director of risk consulting. He stayed just three years with them and re-joined Marsh in his old role for another five years. By then, he had grown stale in the business after almost three decades in the same field. Today, Park Moon works on a retainer with international German insurer, HDI Global.