A break in the emotional cloud that had enveloped my whole being came later that night when my son reached out from Scotland. I had just held the first New Year’s Eve party without my mother who passed away earlier that month. He sent a message that, despite its utter simplicity, resonated deeply with the fragile state of my soul and the turbulent mood of the world. He wished me a “good 2026.” The phrasing struck me with startling perspicuity; it felt appropriate, realistic, and profoundly correct in a way that conventional well-wishes never could. It wasn’t a superficial ‘happy new year,’ which felt laughably optimistic given the circumstances. It wasn’t an overly ambitious ‘prosperous one,’ suggesting material gains while the emotional ledger was deep in the red. Nor was it burdened with the hollow, inevitable broken promises of new year resolutions.

Just good.

Good, I realised with a sudden gratitude, was enough. Good, in fact, was perhaps the highest aspiration one could genuinely hold. Good was, arguably, even hard to achieve, given the escalating, visible fractures in the once-solid political bedrock of Europe and the strained, essential unity of NATO. The global landscape was a cauldron of relentless turmoil, driven primarily by the increasingly destabilising Trumpian edicts of “might is right”—a cold, brutish doctrine in which the concept of a traditional ally or perceived or manufactured foe is rendered utterly meaningless, of no consequence whatsoever to the wannabe dictator’s sweeping, aggressive land-grab hallucinations.

In this shifting, cynical environment, the West’s much-vaunted “rules-based order” had become an irrelevance, a casualty of its own hypocrisy. Its effective death occurred the moment the supposedly compliant vassal states—the smaller nations reliant on the framework—realised with chilling clarity that their own complicity in using this convenient slogan was backfiring spectacularly on them. The sickening, undeniable realisation dawned that it wouldn’t be just the traditional third-world countries subjected to modern-day colonisation or resource exploitation; they, the so-called loyal allies, too, would be strategically targeted, destabilised, or dismantled if they possessed any resource or geographical advantage of value that the declining hegemon desired. The rules, it turned out, only applied to those without the capacity to break them.

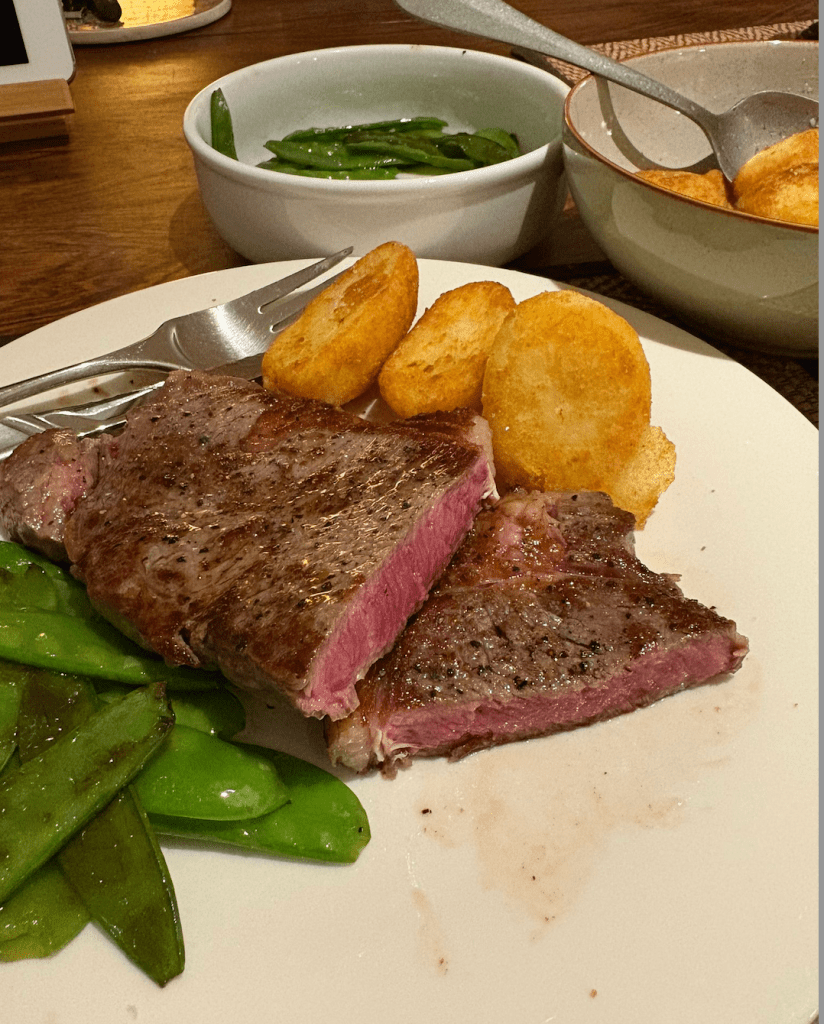

Amidst this gloomy contemplation of personal loss and international decay, the accompanying photograph he sent served as a calm, visceral anchor. It captured him raising his glass to me—a silent, digital toast—in front of the perfectly cooked plate of steak he had just prepared. The image, warm with domestic light and the simple effort of a son caring for his father, improved my mood instantly. It offered a simple, grounding counterpoint, a tangible reminder of caring and love that stood in defiant opposition to the cold, abstract anxieties of political collapse and the heavy, pervasive shroud of recent loss. The personal, I recognised, was a necessary outpost against the gathering, gloomy threats of the political world.

“Three minutes each side, right, and rest it for three minutes?” I asked, revealing the method I would have cooked the steak.

“One minute 20 secs, each side on hot pan, then under foil and cloth to rest,” he replied.

“Rest about eight to ten minutes,” he added.

“Let the rest do the rest,” he suggested.

I looked at his photograph again. His face reflected a deep calmness that soothed me. His countenance was a study in profound peace, a mirror of serenity that belied their recent sorrow. A calm reflection of enviable contentment radiated from him, an almost transcendent acceptance of the circular world, death follows life and then, rebirth. This tranquility was his silent, yet powerful, message to his father: a solemn assurance that the current of life would continue, and with it, a reminder for his father to rest his troubled mind and weary body.

Let the rest do the rest.

The arrival of 2026 was marked not by jubilant expectation, but by a quiet, profound acknowledgement that “good enough” would have to suffice, a concession made in the wake of a loss that had reshaped my new reality. My mother’s demise, occurring less than a month before the arbitrary turning of the calendar page, had cast a long, tender shadow over the new year.

The preceding weeks had already been a brutal initiation into a world without her physical presence, culminating in the first Christmas and the first New Year’s Eve—celebrations historically anchored by her warmth and energy—that now felt strangely hollowed out. Yet, these were only the beginning. The year ahead would stretch out, a series of painful yet necessary “firsts” waiting to be encountered, each a fresh reminder of her absence: the first Chinese New Year gathering, where her gentle smiles and laughter and delight to clink wine glasses would be sorely missed; the first Easter, stripped of the joy she brought to family gatherings; the first birthday celebrations, where her presence and unwavering attention would be a poignant gap; and, most heartbreakingly, the first Mother’s Day, now a commemoration of a life that was.

She was more than just a family member; she was the indisputable matriarch, the strong, unwavering pillar upon which generations had leaned. Her loss was not just personal grief, but the shattering of a lineage milestone—she was the first and, to this point, the only centenarian in our family, and now, a memory to a life lived fully, rich with experience, wisdom, and boundless love. Stepping into 2026 meant stepping into the immense space she had left behind, navigating the quiet echoes of her life could bring more bouts of emotional outpouring.

The outward expression of loss, the public mantle of mourning and death, was but the surface layer. Yet, beneath this visible grief, a deeper truth was struggling to be revealed. Like the technique of pentimento—where earlier images or brushstrokes, long painted over, begin to show through the succeeding layer of paint—so too did the faint, true picture of her great personal stories begin to emerge. The layer of recent sorrow was thin enough to allow the essential, underlying canvas to be seen: a life that was richly and deliberately painted with the indelible colours of motherly love and profound personal sacrifice. This was the enduring masterpiece, the genuine portrait of a mother’s love that time and death could not diminish. It was the legacy that persisted beyond the grave, offering comfort to the living and a final, peaceful farewell.

The sense of her enduring presence was recently heightened by a visit, a few nights ago, during the last half hour of her final day in this realm—the 49th day of her passing. Almost asleep, a sudden, unmistakable whiff of fragrance jolted me from my stupor – that of her favourite white flowers from our childhood home in Penang. This fragrance, similar to the orange jasmine here in Adelaide, typically blooms in spring or early summer, and a check the following morning confirmed the neighbour’s plants were not in bloom. Furthermore, the scent was definitively internal, as the Mrs insists on tightly shut windows to eliminate dust.

Let the rest do the rest. This simple phrase now carries a profound message, suggesting a necessary surrender to the natural process of grieving and healing.

Ahma, may you rest in eternal peace.