“The AWO is coming to town in early September,” the old man yelped excitedly, his voice cracking slightly with anticipation. He had been looking forward to this for months, ever since he first heard whispers of the Australian World Orchestra’s upcoming tour.

“Nah, they never come to a small town like Adelaide, unless… you mean the Adelaide Wind Orchestra?” his niece said, a mischievous glint in her eyes. Steph knew her uncle well; he rarely spoke of local ensembles, and his enthusiasm usually pointed to something far grander. Her tongue-in-cheek comment was also a playful jab at his consistent disinterest in anything but the most prestigious international acts. Steph, on the other hand, possessed a deep, unwavering passion for music and art that had shaped her colourful life. She had budding success in carving a name for herself in Adelaide’s vibrant music scene, her reputation as a talented singer/musician preceding her. Her journey, however, hadn’t been without its detours. Her parents, like many in traditional Asian societies, initially held less supportive views of her musical aspirations. They had, with good intentions, steered her during her high school and university years towards “more financially secure” fields, explicitly mentioning medicine and dentistry as ideal career paths. The arts, in their view, were not reliable “rice bowls”; the inherent uncertainties and financial challenges faced by musicians were seen as unrewarding obstacles for ordinary individuals, and the potential earnings were considered paltry compared to the predictable high monthly incomes offered by established white-collar professions. To appease them, or perhaps to please them, Steph had indeed pursued and obtained a degree in physiotherapy, even practicing for a time and currently, doing it part time to help the aged. Yet, the siren call of music was too strong to ignore, and eventually, she found her way back to the path she had always loved – making music.

“The Australian World Orchestra, of course!” he bellowed, a characteristic scrunching of his eyebrows deepening the lines on his forehead, making him look considerably older than his advancing years. He often did that when emphasising a point. “Actually, I call it the Australian World-class Orchestra,” he added, chuckling to himself, clearly proud of his personal moniker for the renowned ensemble.

The Australian World Orchestra, of course. It was an institution, a national treasure formed a remarkable fifteen years ago. Their unique model involved inviting the finest Australian classical musicians, those who had forged illustrious careers plying their skills in the greatest orchestras and ensembles around the globe, back to their home country. These prodigal talents returned to perform to consistently sold-out concerts, a testament to their supreme artistry and the deep appreciation of Australian audiences. The AWO’s leading musicians were drawn from the ranks of truly prestigious ensembles, a veritable Who’s Who of classical music: the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, the Singapore Symphony Orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Scottish National Orchestra, and, of course, Australia’s own esteemed state orchestras and ensembles.

“Let’s go!” Steph exclaimed, her earlier teasing forgotten in a wave of pure excitement. “Mahler 4 and 5 in one concert. What a treat!” Her almond eyes sparkled at the prospect of experiencing such monumental works performed by an orchestra of this caliber.

“Great! I’ll get it organised,” the old man said, already mentally planning the logistics. Traveling interstate to attend classical music concerts or art exhibitions was, for him and Steph, a would-be cherished pastime, a true indulgence, if not for the prohibitive cost. Even so, it was an adventure they had embarked on many times, creating a kaleidoscope of shared memories for their family album. Adelaide, where they lived, was indeed a wonderful place: beautiful, peaceful, safe, clean, and notably affordable. However, the very characteristic that made it so appealing – its smaller size and quiet charm – also meant a paucity of truly grand events, such as the AWO concerts. This scarcity necessitated interstate travel if they wished to immerse themselves in performances by big-name musicians or witness sports legends in their prime.

Over the years, the old man, driven by his passion for classical music, had journeyed to all major Australian cities and many regional towns such as Bendigo, Bathurst, Barossa Valley, Bridgetown in WA, Cairns, Orange, Mount Barker. He had attended many fantastic concerts, vibrant music festivals, and prestigious competitions, including the Australian Young Performers’ Awards, and even ventured across the Tasman Sea for the Adam Cello Competition in Christchurch, New Zealand and to cities like L.A., New York, Seoul, Singapore, and Xiamen, Hong Kong, Taiwan in China, Chichester and London in England, Edinburgh and Glasgow in Scotland. On a few memorable occasions, these trips had been grand family affairs, with his beloved mother and sisters joining in the excitement.

Many of these cherished memories were chiselled into his brain during captivating overseas trips, each holiday leaving an indelible impression of shared adventures. The thrill of exploring new horizons together often began with a delightful food safari, a culinary preamble to the much-anticipated culmination: a concert in one of the world’s most hallowed venues. From the iconic grandeur of London’s Royal Albert Hall and the intimate acoustics of Wigmore Hall, to the iconic stages of New York’s Carnegie Hall, Amsterdam’s Royal Concertgebouw, and the historic Rudolfinum in Prague’s Old Town, each performance was an unforgettable experience. The operatic splendour of Milan’s Teatro alla Scala and the modern architectural marvel of Rome’s Auditorium Parco della Musica also provided equally magical backdrops for these musical pilgrimages.

Beyond the concert halls, the invigorating pursuit of art also beckoned. New York’s Metropolitan Art Museum and the MoMA offered an immersive dive into diverse artistic expressions, each stay in New York requiring multiple visits to these must-see destinations while the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam ranked highly for the old man, who was fond of the masterpieces of Dutch masters like Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Van Gogh. Great works such as “The Night Watch” and “The Milkmaid” stood out as particularly compelling for him. He was thankful to Catherine the Great for creating the Hermitage Museum that adjoined her Winter Palace in St Petersburg, with its astounding three million pieces of art, it might be considered the largest repository of paintings in the world; the intimate viewing of Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper” in Milan and Michelangelo’s breathtaking frescoes in the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City were equally, if not more, profoundly memorable. The allure of ancient civilisations also drew him and his Mrs to the National Palace Museum in Taipei, where China’s invaluable treasures offered a glimpse into a rich and storied past. They were there for three days in a row yet were unable to see every room there was on offer.

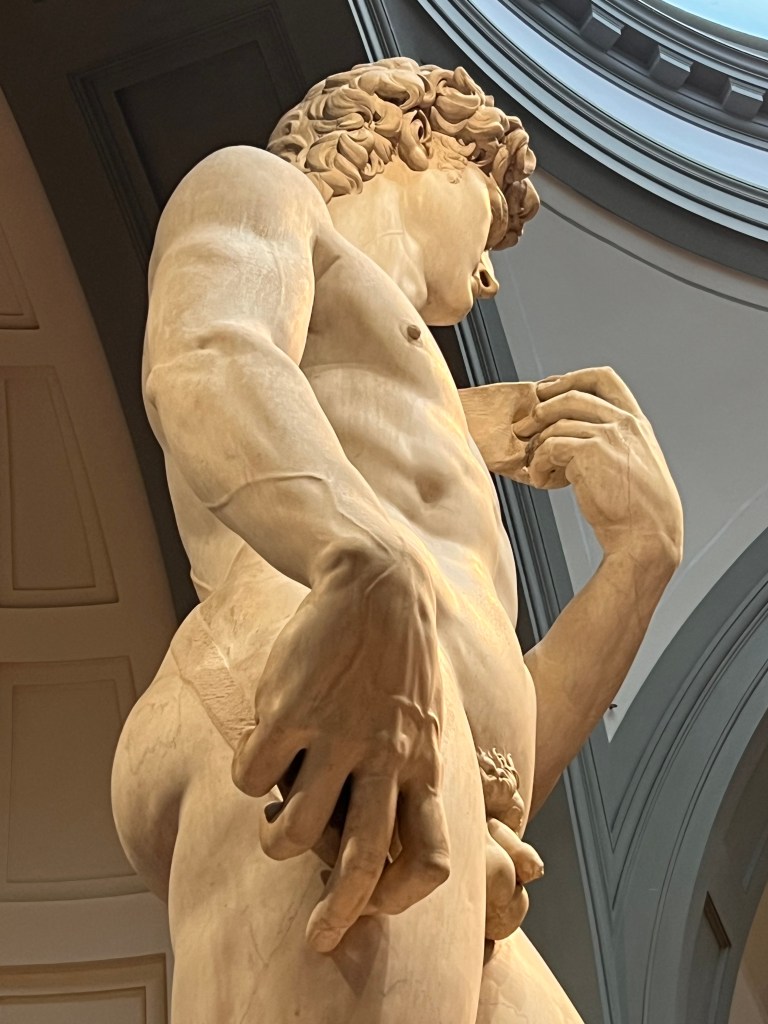

Indeed, there were simply too many extraordinary experiences to recount exhaustively, but certain marvels left an uneraseable mark. Michelangelo’s awe-inspiring marble statue of “David” in Florence, a testament to his remarkable talent, was a particular highlight. Equally captivating were the numerous supreme works by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the leading sculptor of the Baroque period, housed in Rome’s magnificent Borghese Gallery. His unbelievable creations, including his powerful renditions of “David” and “The Rape of Proserpina,” showcased a masterful blend of emotion and dynamic movement.

Closer to home, just back in February, a quick trip to Melbourne and Sydney brought joy to several family members. This particular journey was timed to coincide with the esteemed Singapore Symphony Orchestra’s inaugural and highly anticipated visit to Australian shores, marking a significant cultural exchange and another cherished shared adventure.

While sitting at his desk remembering his adventures and penning them down for me, his mind drifted to something even closer to his heart – his mother’s dementia. Outside, the warm afternoon light, which had moments before streamed through the window and illuminated his parchment, suddenly faltered. A colossal bank of charcoal-grey clouds rolled in from the west, swallowing the sun whole. It was as if a celestial stagehand, responding to an unseen director’s abrupt and barked command, had swiftly changed the entire set and adjusted the lighting, plunging the room into a muted, introspective twilight. The sudden shift in ambiance mirrored the abrupt change in his own emotional landscape, from the exhilarating highs of recollection to the melancholic weight of present reality. The once-bright world outside his window now seemed to grieve with him, its golden hues muted to a somber palette, reflecting the somber turn of his thoughts.

Dementia is an insidiously cruel disease that relentlessly ravages the mind, inflicting immense suffering on the patient. They endure profound frustration, confusion, aggression, and even vivid delusions. The very essence of their independence is eroded, stemming from a tragic cognitive loss and the agonising inability to communicate their most basic needs, whether physical or emotional. It is a slow, cruel descent into a world where their own thoughts betray them, leaving them feeling isolated and bewildered.

This cruelty extends its reach far beyond the individual, casting a dark shadow over their loved ones. Family members are forced to bear witness to a gradual, heartbreaking decline, a beloved mind slowly succumbing to a toxic transformation. They often become targets of hurtful scoldings and nasty accusations, flung by the very person they cherish, whose mind has become a labyrinth of suspicion and paranoia. The emotional toll on caregivers is immeasurable; they are trapped on a relentless spiral of grief, stress, and despair. The once-familiar connection is strained, replaced by a painful chasm of misunderstanding, especially at the early stages when awareness of the disease has not formed.

In more severe cases, the suffering can escalate into frightening outbursts of physical or verbal aggression. Loved ones may face hitting, kicking, scratching, or relentless yelling, all from someone they once knew so well and loved. The physical and emotional scars left by these incidents can be profound. For the patient, true relief from this torment often arrives only much later, at the stage of total cognitive loss, a tragic surrender to the disease’s ultimate grip. Yet, even then, the grieving process for their loved ones does not cease. It continues, a lingering ache for the person they lost long before their physical presence faded. The memories of the struggle, the pain, and the grieving for the loss of the loved one’s mind remain.

The twilight years often cast long shadows, and for the old man, they were particularly deep, mirroring the shrinking, fragile form of his 103-year-old bed-ridden mother. Her once vibrant spirit was now a wisp, her forehead contorted in a perpetual grimace of pain or confusion, her words a jumble of inaudible sounds, often making no sense to him. Each day was a quiet vigil, the silence and repetitiveness, representing the relentless march of time and the slow erosion of a life once lived with vigour and purpose.

His mind turned to a particular night that was different, a peculiar shift in the now familiar rhythm of her dementia. She was wide awake, her eyes, though clouded with age and heavy from exhaustion, held an unusual glint. And she was speaking, not with the profound wisdom one might expect from a centenarian, nor with coherent sense, but with words that seemed to hold a peculiar meaning only for her. That night, she was chatty, a rare occurrence. Short sentences, strung together with a strange, almost childlike rhythm, flowed from her lips. She even mentioned possessing “ka tze,” two rings, adorning her fingers, a detail that surprised him. Her descriptions of her meal were equally vivid and unusual: her fried noodles were cooked with “dae wu bee” (dried tofu skin) and “ho mee” (dried prawns), specific but unexpectedly wrong observations.

Her right thigh was a persistent source of agony, and she was preoccupied with massaging it as she ate, her movements slow and deliberate, each mouthful a monumental effort. Yet, amidst her struggle, a new fixation emerged. She reached for the pillow that was supporting her leg, her still rather strong right hand attempting to pull it out from beneath her. “Deh kak sei deo,” she kept repeating in her Ningbo dialect, “egg shells are shattered.” Her voice, though weak, held a strange insistence as she tugged and even hit the pillow repeatedly, convinced that it contained egg shells or that it was egg shells. She explained that these shattered shells held the key to alleviating her pain, a bizarre, nonsensical yet desperate hope. Her energy, much like a faulty light bulb, flickered on and off, moments of unusual clarity and action interspersed with long stretches of quiet exhaustion, a poignant reflection of her fading life.

A ping from his phone alerted him to an incoming message, turning his attention away from the bleakness of dementia. A friend had sent him a note saying no one is great at birth – it’s our behaviour and actions that make us great. The old man disagreed.

“I think our mothers were great at birth. The severe pain during labour that they endured is surely a measure of their great love, at a time when they did not even know us.”

But, the matter of dementia soon dragged him back to his mother’s room in the nursing home.

The insidious grip of dementia had stolen his mother’s precious memories, including those of her son. The man standing before her, a reflection of her own youth and steadfast nurturing, was now a stranger. He, whom she had brought into the world and guided through the lean, challenging years of the 1950s and 60s in post-war Penang, was now met with a chilling detachment. “Go away, I don’t like you,” she would declare, her voice tinged with an alien ferocity, as she repeatedly tapped her head and sometimes tugged at her hair. Even more severe were the venomous pronouncements: “Pe-o-tze sa, zong-sa” – “A prostitute’s son, a wild-born.” These cruel epithets, utterly devoid of truth and verifiably false, had somehow found a deep, unshakeable root in the fractured landscape of her mind. Had he not possessed an understanding of the relentless and unforgiving nature of the disease, its capacity to twist and distort the very essence of a person, his own self-esteem would have been irrevocably shattered by the weight of her words. He would have internalised her accusations, allowing them to corrode his sense of identity and worth. But he knew, with a heartbreaking certainty, that these were not his mother’s true sentiments, but rather the cruel echoes of a mind under siege.